A Plate of Diplomacy

WANA (Oct 23) – Sometimes, politics is shaped more over a plate of food than at negotiation tables or official meetings. “Food Diplomacy” refers precisely to this concept: a method used by countries to soften relations and capture the attention of the world, with politicians utilizing it to reduce tensions and build new bridges.

In his recent trip to Cairo, Iran’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Seyed Abbas Araghchi, engaged in this type of diplomacy by dining at the local restaurant “Abou Tarek” and enjoying the famous Egyptian dish, koshary.

Photos of Araghchi at a restaurant in central Cairo were covered by some Arabic media. Sharing his experience on social media, he wrote, “Koshary is a very delicious dish made without meat. I recommend that fans of Arabic cuisine try it.” However, it was his final comment that drew more attention: “There’s a need for an Egyptian restaurant in Tehran.”

This seemingly simple statement can be interpreted as a sign of readiness for cultural ties between Iran and Egypt, and perhaps a subtle invitation to open a new chapter between the two countries, whose relations have been strained in recent years.

In the past two decades, relations between Iran and Egypt have been far from warm, but Araghchi’s gesture could be the beginning of cultural bridge-building. In reality, food is more than just sustenance; it is a universal language through which communication with others can be easier than formal negotiations. In other words, a plate of koshary might just help bridge the gaps.

Since the advent of diplomacy and the modern nation-state in the 17th century, food has been an important element in diplomacy. It serves as a tangible symbol that helps create a positive image in the international community and is ideologically used to reduce tensions, embodying the concept of “soft power.” Soft power involves a set of mostly intangible factors like charm, influence, image, or ideology, aiming to create an appeal that persuades without force.

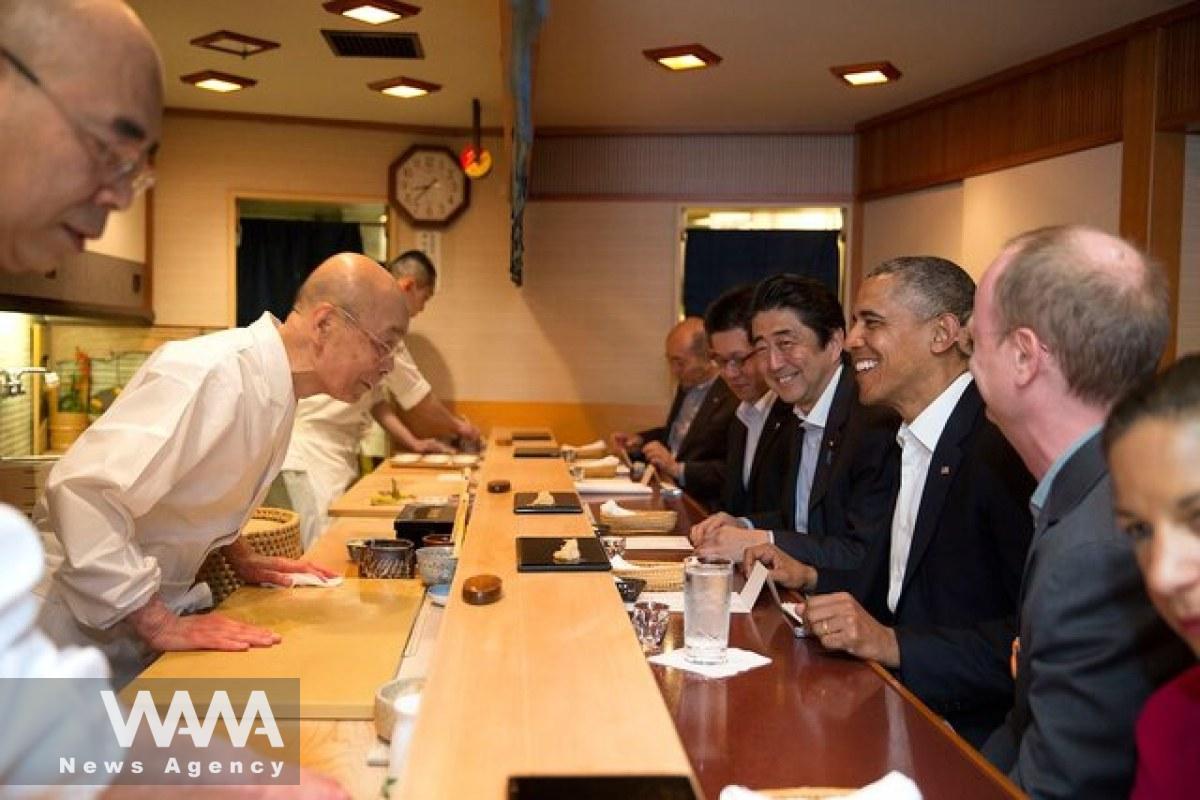

Barack Obama and the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the restaurant of renowned sushi master, Jiro Ono. Social Media / WANA News Agency

While food diplomacy (gastrodiplomacy) is an old concept, it has taken on new terms in recent years. Paul Rockower describes food diplomacy as “winning hearts and minds through stomachs.” Essentially, food diplomacy, also known as culinary diplomacy or the politics of food, is a form of public diplomacy in which food is used as a tool for cross-cultural understanding and, with hope, improving interactions at a higher level—between governments, rather than between governments and the general public.

Today, food is even used as a variable for influence, transmitting culture, identity, and messages that can signify either friendship or hostility.

The increasing number of food diplomacy initiatives shows that the value of food in diplomatic relations extends beyond simply hosting foreign guests. Some countries, including South Korea, Japan, and Peru, have launched campaigns to give it a tourism aspect. Certain nations also invest heavily in annual food festivals and campaigns abroad to indirectly promote travel to their countries.

South Korea’s ‘Culinary Diplomacy’ in the Shadow of Kimchi. Social Media / WANA News Agency

“Food Diplomacy,” focusing on the appeal of cuisine, has become one of the most important issues in the tourism industry. It can also foster a sense of unity and national pride in countries facing internal conflicts, bringing people back to the good old days before modernity and globalization, as seen in South Korea’s “kimchi” campaign, where the country hosts diplomatic figures with this dish.

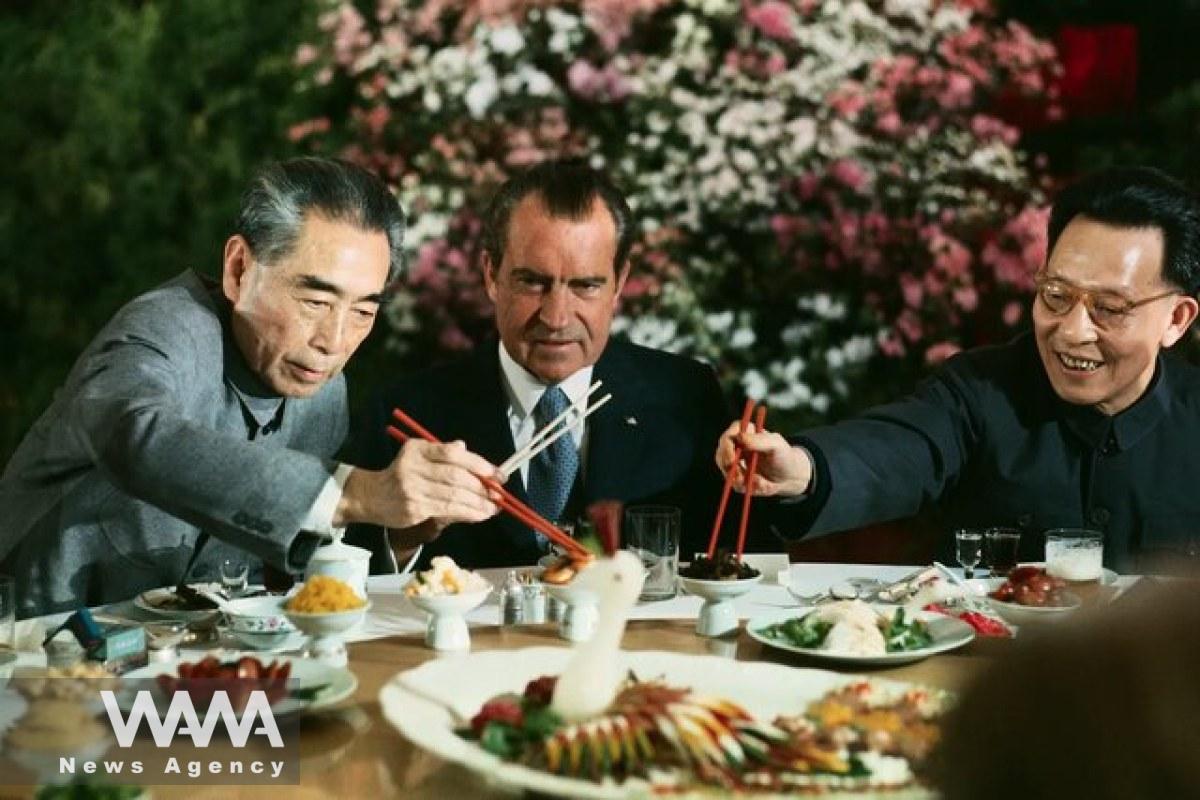

Throughout history, food has played a key role in official encounters, negotiations, and cultural exchanges between nations. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, regarded “table diplomacy” as a central tool for showing power and influence in international discussions and decision-making. The 1972 dinner between U.S. President Richard Nixon and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai—where Nixon skillfully used chopsticks, a rare skill among Westerners at the time—was as important in fostering U.S.-China relations as the more famous ping-pong diplomacy.

Richard Nixon, the then-President of the United States, using chopsticks while Zhou Enlai, the Premier of China, and Zhang Chunqiao, a leader of the Communist Party in Shanghai, hold their chopsticks in front of him during a banquet in China in 1972 . Social Media / WANA News Agency

This strategy has been repeatedly employed by high-ranking officials and ambassadors alike, with its soft power influencing hearts and minds. Sociologist Stechapel Sokol noted, “People might not be able to tell you much about their history, but they know what their food is.”

For instance, Germany’s new ambassador to Tehran, Markus Potzel, recently released a video showing him buying his favorite doner kebab from a restaurant in Tehran—the same one he visited 20 years ago. This simple act was more than just a meal; it sent a message of cultural connection that transcends time and place.

The New German ambassador, Markus Potzel, returning to the same restaurant in Tehran after 20 years to buy his favorite doner kebab. Social Media / WANA News Agency

Moreover, food diplomacy can effectively help resolve internal disputes. In many countries, including Afghanistan and Iraq, NGOs have used food to bridge divides between different social groups and even mediate conflicts. Local food festivals create opportunities for people to interact and share their cultural differences, helping reduce tensions and foster greater solidarity in communities facing internal struggles.

In conclusion, food is more than just sustenance; it is a tool for communication, cultural exchange, and even narrowing political divides. With its rich and diverse culinary tradition, Iran can leverage this soft power to enhance its standing in the world. Perhaps, one day, food diplomacy will play as vital a role in Iran’s foreign policy as it does in other countries.

The Secrets of Iranian Cuisine You Need to Know!

WANA (Oct 17) – Imagine a land where people make history with the very food they eat. For Iranians, each bite is more than nourishment—it’s a narrative of culture, philosophy, and art. In Iran, cooking is not just an art; it’s a language, a way to express emotions, relationships, and even the philosophy of life. […]