Hijab in Iran: A Continuing Challenge

WANA (August 05) – The use of clothing in any society is shaped by its specific standards and patterns, reflecting its unique culture and religious beliefs. These standards and frameworks evolve due to the influence of various cultures, changing societal beliefs, and shifts in governance and dynasties, and Iran is no exception to these changes.

In Iranian society, the concept of “hijab” is prevalent. The hijab refers to covering and creating a boundary, primarily used to cover the body. For women, hijab should be worn in a manner that does not create sexual attraction for non-mahram men (men who are not close relatives).

Today, the typical attire for Iranian women in urban areas includes manteaux (long coats), trousers, and scarves or shawls, while some women opt for the chador (a full-body cloak). In rural and nomadic regions, Iranian women often wear traditional clothing.

Reviewing the history of Persian attire can help one better understand this topic. It is important to remember that since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, women’s clothing has been one of the most contentious issues within Iranian society and among women.

Following the Islamic Revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran established a framework for women’s Islamic and official dress codes. This code mandates that women wear appropriate clothing in the presence of non-mahram men, ensuring that their bodies are not visible and only their faces and hands up to the wrists are exposed. Over the years, these defined boundaries have evolved due to the influence of Western culture.

Recent years have seen significant cultural changes in the realm of Islamic hijab. Clothes have become tighter and more revealing, scarves have been pushed back to reveal hair, and manteaux (long coats) and trousers have become shorter. Some women have completely abandoned head coverings, such as scarves and veils. These transformations in Islamic dress have accelerated in recent times.

The death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was taken to a police station for her allegedly inappropriate attire by Iranian standards, brought these issues to the forefront. At the station, Mahsa suffered a brain shock and died. Her death sparked several months of street protests.

Among the protesters’ demands, the primary grievances were against the “mandatory hijab” and the presence of the “Morality Police”. The Morality Police in Iran are responsible for enforcing Islamic dress codes in public spaces.

While the street protests have ended, the debate over the enforcement and observance of hijab laws in Iran continues at various levels. The government shows no intention of retreating from the implementation of Sharia law, while proponents of Western culture resist adhering to these Islamic regulations.

Iranian women walk in a street in Tehran, Iran, October 3, 2022. WANA (West Asia News Agency)

Three Common Beliefs About Hijab in Iran

1. The type of hijab common in Iran is unique to the country and is not followed in the same manner in other countries.

2. Before the arrival of Islam, Iranian women had different forms of attire and did not observe such coverings. The advent of Islam imposed these clothing restrictions on us.

3. Everyone should have the freedom to choose their attire and appear in society as they wish; enforcing Islamic dress codes is not appropriate.

Islamic scholars argue against the first and third beliefs, stating that every country defines its own framework and boundaries for dress codes. It is natural for these laws to align with the country’s culture, religion, and type of governance. Non-compliance and breaking societal norms come with consequences. The demand to follow these laws is not limited to women.

Research indicates that over 150 countries have dress code regulations tailored to work environments and activities. These rules, which undoubtedly limit some individual freedoms, are enforced in many countries to maintain a safe and psychologically comfortable environment. For example:

– In Malaysia, men are subject to dress code restrictions and are not allowed to wear shorts.

– In countries like Thailand and Singapore, wearing sleeveless shirts on the streets is prohibited and can result in fines.

– In Iraq, wearing jeans is restricted for both men and women in certain areas.

– Wearing blue jeans is banned in North Korea.

– In Brazil, any act of public indecency or displaying body parts can result in imprisonment for three months to one year.

– In Melbourne, Australia, it is forbidden for men to wear clothing styled for women.

– In Greenville, USA, wearing any shirt that reveals part of the stomach is not allowed.

– In Canada, any attire deemed against public decency is prohibited.

– Various dress codes for women and men exist in workplaces, universities, religious sites, and other settings in different countries.

These examples from around the world illustrate that dress codes are important in many societies, and simply wanting to dress as one pleases is not always a valid reason.

According to most sociologists, the absence of frameworks and laws for appropriate attire can lead to numerous social degradations, including:

– The devaluation of women’s human dignity.

– The loss of psychological peace.

– The diversion of talents due to the lack of recognition of truth and the pursuit of scientific excellence, leading to moral deviations, depravity, and loss of identity.

– Familial consequences such as increased divorce and infidelity.

– Early puberty.

– The spread of social corruption.

Hijab In Across Various Periods

Contrary to the belief that hijab and dress codes in Iran are exclusive to Islam, historical evidence shows that modesty in clothing existed across various periods and religions, even before the advent of Islam in Iran. Here are some historical examples of modest attire from different eras, both before and after the arrival of Islam:

Persian Era: Archaeological studies reveal a seal from this period, showing two women wearing long dresses down to their feet and covered with cloaks resembling short chadors that covered half of their bodies. Another depiction shows women riding side-saddle with a rectangular chador over their entire bodies, wearing long dresses underneath and reaching their ankles.

Achaemenid Period: Women depicted in the Argilli relief in western Turkey are seen wearing simple long-sleeved garments from neck to ankle, with a head-covering similar to a chador that was slightly shorter and reached below the knees.

Timurid Era: Women wore not only local headscarves and traditional clothing but also chadors and veils that concealed their faces.

Safavid Era: Women wore colorful silk floral dresses with long coats and a belt, enhancing the beauty of their attire

Qajar Period: Women’s attire included slit dresses, short layered skirts, and long scarves decorated with silver or gold belts for a distinctive appearance.

Pahlavi Era: Women’s clothing became significantly different, featuring long single-piece dresses without chadors or veils, often accompanied by hats.

Iranian women’s clothes in different periods/ Social media / WANA News Agency

According to many believers across various religions and numerous social and human rights scholars, modesty and hijab are not confined to a particular time or place in history. They argue that by observing them, both men and women can protect society from many dangers.

Most importantly, preserving the hijab safeguards the family unit, the cornerstone of society, from potential threats. On both individual and social levels, the hijab contributes to increased security, respect, and even progress.

Is the Hijab a Hindrance or a Pathway to Advancement?

Dr. Alavi, a 40-year-old woman with a Ph.D. in philosophy, believes that “modesty and hijab are two crucial elements of the identity of Iranian Muslim women. The oppressive global system has always aimed to eliminate these elements, ensnaring men and women in base desires to strip revolutionary thought from societies, thereby extending its soft power over countries.”

Dr Alavi, a 40-year-old woman with a PhD in philosophy/ WANA News Agency

Proud of her chador, Dr Alavi views hijab not as an impediment to progress but as a facilitator of it. She argues that observing hijab prevents others from objectifying women, creating an environment where women can showcase their talents and capabilities without fear of lewd and gender-biased gazes.

This perspective fosters opportunities for women to excel in social settings, promoting their abilities and contributions to society without distraction or disrespect.

Contrary to widespread misinformation, Iran might serve as an exemplary case. Comparing the status of women before the revolution, when hijab was not mandatory, to their status after the revolution under Shia Islamic governance provides some answers to this significant question.

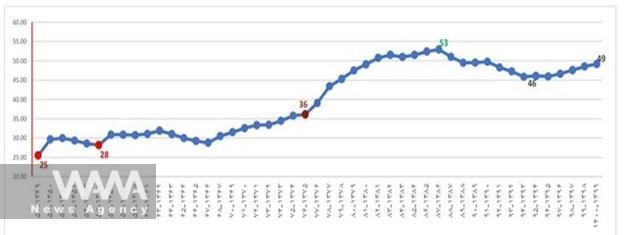

Literacy Rates: According to the World Bank, the illiteracy rate among Iranian women dropped from 50-60% before the revolution to less than 10% after the revolution. Additionally, the World Economic Forum reports that Iran ranks first globally in educational equity between girls and boys.

Higher Education: Over 60% of Iran’s student population are women, indicating their significant presence in higher education.

Sports Achievements: Iranian women have won 3,302 medals in recent international sporting events.

Judiciary: There are over 1,121 female judges active in Iran.

Publishing: There are more than 9,500 female authors and 840 female publishers in the country.

Healthcare: Post-revolution, over 95% of births have been attended by obstetrics and gynaecology specialists.

Life Expectancy: The life expectancy for women has increased from 57 years to 78 years.

Film Industry: There are 903 female filmmakers active in Iranian cinema.

Academic Roles: The percentage of women in academic faculty positions has increased from 14% to 30%.

Sports Medals: The number of medals won by women has surged from 2 before the revolution to 800.

Specialist Doctors: The proportion of female specialist doctors has risen from 9% to 30%.

Leadership: There is a greater presence of women in roles such as ministers, parliament members, and managers compared to before the revolution.

Despite the fact that hijab is not mandatory in many Islamic countries, the progress of women in these nations in various fields cannot compare to the advancements made by women in Iran.

The narrative surrounding Islamic dress codes seems to have become a tool for Western powers to undermine rulers and create divisions among Islamic nations. Is the push to impose Western culture in Islamic countries truly out of concern for women’s well-being and a better life, or is it a long-term political strategy for greater control and influence?

This question remains critical as it highlights the complexities of cultural and political dynamics at play, especially regarding the portrayal and treatment of women’s issues in different parts of the world.

Women’s Participation in Education/Social Media / WANA News Agency